- Home

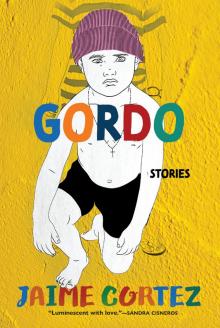

- Jaime Cortez

Gordo Page 3

Gordo Read online

Page 3

Miguelito is quiet, then he says, “I don’t know.”

“Usually, you get beat up,” says Pa.

“But my shoulder’s broken,” he says.

“Let me see your shoulder,” says Pa. “Can you lift your arm?” Miguelito raises his arm. Dad gets Miguelito by the elbow and moves the arm up and down, bends it back, then moves it in circles.

“Don’t worry, Flaco,” my pa says. “Only scratches, nothing broken. Tu estas perfectamente bien. Do you want me to clean your cuts and put mercurio on it?” asks Pa.

“No,” says Miguelito. “Mercurio hurts, and it looks like blood.”

“Then go home to your mami, stop crying, and start training so you can win the next fight.”

“I didn’t lose the fight,” says Miguelito. “It only looks like I lost. He dropped me.”

“Look at your face with blood. Look at Gordo’s face. Who won?”

“Your dog bit me,” says Miguelito. Dad looks at the bite marks.

“Pfft. No es nada. Lobo was just playing. Baby bites. Go home, wash it, and get some mercurio on it, like I told you.”

Miguelito looks at my pa like he wants to say something back, but he don’t say nothin’. Miguelito gets up and fixes his cape and then walks past me. As he passes, Miguelito mad dogs me. I say I’m sorry one more time. Miguelito looks at me and he talks, but he doesn’t make a sound. I can see his mouth moving slowly, and he is saying: “Fuck you.” I look down at my pretty silver boots.

“Gordo,” says my pa.

“What?” I ask.

“You won.”

Pa squeezes my shoulder and smiles at me. Then he walks away. I sit down on the mattress. I reach back and open up the laces on the back of my mask. I pull it off. Aah. My hair is wet. My face is hot. The air feels good, but I don’t feel good. Lobo walks back to me and lays down next to me on the mattress. He still has a little blood on his mouth.

“Hey, Lobo,” I say. He looks at me. He looks kind of sad.

“I won,” I tell him. “I won.”

Chorizo

The dogs are melting. Lobo is lying on the porch with his pink tongue hanging out. Chiquita is hiding under the car with her ears down. Everybody is hiding from the sun except for me. I’m riding my bicycle so I can feel some wind when I pedal. It’s not working too good. Past the tomato fields, I can see this family walking along San Juan Highway. Right away I know they ain’t doing so good. We’re not rich or nothing, but they look super poor, even from far away. They’re walking, so obviously they don’t have no car or even a bike. I see two adults and two kids. The mom and dad have big Santa Claus sacks on their backs. The two kids have smaller sacks. They turn off of the highway and start walking up the dirt road to the Gyrich Farms Worker Camp.

“Somebody’s coming!” I tell my nana. “Who are they?” Nana looks out the kitchen window. “Only God knows, mijo.”

“Are they in our family?” I ask.

“I don’t think so, Gordo.”

“Do you think they’re lost?”

“Maybe. We’ll see,” she says.

They get closer and I can see them clearly. They’re indios. They’re darker than Hershey Bar Pancho, and he’s the blackest in the family. Their faces are sweaty. The little girl wears huaraches, and her feet are dirty from the road. They get to my nana’s house and stand in a row. I say hi. They look embarrassed.

“Hola,” I say.

Nana comes out. The mom and dad smile at her.

“Buenos dias, señora,” the father says. His voice sounds like a joke voice. Like he’s trying to sound like a girl. I look at him more carefully. His boots are tiny, smaller than mine. I never seen such a tiny man. He holds out his tiny brown hand and Nana cleans the soap off her hands, and they shake.

They introduce themselves. The father’s name is Xaman. The mother is Yuritzi. I never heard names like those before. Those are Star Trek alien names.

“Señora,” says the father. “We’re sorry to bother you, but we have a great favor to ask.”

“Tell me.”

“If you could, señora. Would you make us a gift of a glass of water?” I never heard of nobody giving a gift of water. That would suck, to get a gift that was just a glass of water.

“Yes. Of course. Please sit here on the porch, out of the sun.”

“Gracias. The children, they’re very thirsty.”

“It’s so hot today. Poor kids look tired,” says Nana. She pats the girl’s dusty head. “I’ll get a nice pitcher of cold water.”

Nana goes into the kitchen. The family sits down in the shade of the porch. Lobo is too hot to bark. The two kids sit down on their sacks. The little girl stares at my bike like she’d never seen a bike before. The boy could be my grade or maybe just a third grader. You can’t really say, because even though his head is really big, his body is tiny. His hair shoots up like Woody Woodpecker’s. I can hear Nana cracking the ice and then she comes out with a pitcher of water and four stacked glasses. She gives everyone a full glass, and they drink it to the bottom. Nana fills them up again and they finish it all real fast.

“Nana, they’re super thirsty,” I say. “Maybe we should let ’em drink from the hose.”

“Niño. Be quiet.” She says to me and says to the father: “I’m sorry, señor. He talks too much. Please excuse him.”

“No, he’s right,” says Xaman. “We could probably drink a gallon each.” Yuritzi smiles and nods her head.

“We’ve been walking since the little store in town,” she says. She also has the voice of a little kid.

“Ave Maria,” says Nana. “You’ve been walking from Sanchez Superette? The red store with the wooden bear in the front?”

“Yes. We walked from there. We’re looking for work. Do you have work, señora? We’ll do anything.”

“This isn’t our rancho. We’re only workers here, señor.”

“Do you think your jefe would hire us? We’ll do anything.”

“You might be in luck. It’s August. The tomato harvest started this week. Yesterday the migra came with two vans and grabbed a bunch of workers off the tomato harvester to send them back to Mexico, so the jefe might need extra hands.” The little man leans forward and grabs Nana’s hand.

“Do you think maybe you could possibly help us meet your jefe to ask for work?”

“Yes,” says Nana. “It’s heavy work, though, especially on the tomato harvester. They only hire women. Their hands are smaller and faster.” Nana looks at the mom. “Señora, I’ve worked the harvester many times,” warns Nana. “With the heat and the dust and the noise, lots of women faint.”

“No hay problema,” says the father, slapping Yuritza’s shoulder. “This one, she’s like a mule. Strong.” That’s pretty funny. The mom smiles at her feet. When the little girl smiles, I can see all of her front teeth are gone except for the two pointy ones on the side. Every kid in the Gyrich Farms Worker Camp has to have a nickname. I decide hers will be Vampi.

“Our jefe usually passes by in the mornings to load up the water truck at the pump right over there. We can ask him then.”

“Yes, por favor, let’s do that. We have to thank the Virgin for putting you in our path, señora, to help us find work. Gracias.”

“Let’s hope we can get you some work,” says Nana.

“It shames me to ask for another favor.”

“Go on, señor.”

“That building over there. Can we sleep there?”

“That’s for the chickens, señor. I couldn’t let you sleep there. It’s too dirty. There’s fleas. Lice.”

“How about over there,” he asks, pointing to the carport.

“In the carport?” asks Nana.

“We promise we’ll take good care of it.”

“There’s shade, but there are no walls,” says Nana.

“That’s all we need, señora. We’re very tired. We’ll only stay a couple of days, until we find work.”

“I’m sorry we don’t have room in the

house, but it’s tomato season, and we have cousins staying and the house is really full. We’re like sardines, but if you want to sleep in the carport you can.”

“Thank you, señora. May God reward you for this.”

* * *

After resting in the shade and drinking some more water, the family begins taking their stuff out. First, they take out a big blue plastic sheet and lay it out on the dirt. Then they put a big dirt clod on each corner of the sheet. They’re going to sleep on that? They unfold another plastic sheet and with a yellow rope they make a little tent, like if they’re camping. Vampi’s mom gets the hose, turns it on, and—I can’t believe it—Vampi and her brother get naked, completely naked, and she hoses them and soaps and then washes their hair. Nana stomps out of the house, walks over to me, and points for me to go inside, so I do. She follows after me.

“Gordo,” she says. “Stop staring at that family.”

“They’re taking a bath outside,” I say.

“Let them,” she says. “They’re trying to get clean. There’s nothing wrong with that. I’d be happy if you’d take a bath inside or outside or anywhere.” Grandma steps back outside and talks to the mom. I stand near the window and pretend not to watch them all.

“Yuritzi,” says Nana. “Do you and your husband want to use the shower room over there by the willow tree?”

“Yes, gracias.”

“We don’t have indoor toilets here at the camp,” says Nana. “The outhouses are over there for you all to use. There’s paper there already. There is a flashlight in there if you need to use it at night. Also, we don’t have a telephone here. I’m sorry.” The lady and her husband begin to giggle. “Ai, señora,” she says. “It doesn’t matter if you don’t have a telephone. In our pueblo, no one in the family has a telephone. There’s nobody to call!” Nana laughs with them.

“Do you want to use the kitchen? I have a stove and sink and refrigerator if you want to use them.”

“No. That’s fine.”

“Please don’t be shy about asking for anything.”

“Gracias,” says Yuritzi. Nana goes back inside and I follow her. A few minutes later, we hear my grandpa pulling up in his pickup truck. He is home from work. He drives to his usual parking spot in the carport but stops when he sees the family. Grandpa gets out of the pickup. He don’t say hi or nothing to the family. He walks straight into the house.

“Vieja, who are those people?” he asks Nana.

“They just arrived from the other side. They don’t have any place to sleep.” He don’t say nothing. She don’t say nothing.

“Gordo, go outside,” says Grandpa.

“But Grandpa,” I say, “Nana just told me to stay inside.”

“And I’m telling you to go outside. And don’t bother those people.”

* * *

I step out and ride my bicycle around the house like a merry-go-round. Past the window, I hear my grandparents talking all mad in the kitchen. Past the carport and the family is stacking up some firewood for a fire. Past the window and Grandpa is saying something about how this is his house. Past the carport and the dad is down on the ground, burning up a little dry grass under the wood. Then it’s Nana stacking away the dishes and getting rough with it. Then it’s Vampi and her brother stealing a few tomatoes from the field and whoa—Xaman got a nice fire going. I stop the merry-go-round to have a good look. I love fires so much.

From her sack, the mom pulls out a brown grocery bag. She takes out an onion, dried masa for tortillas, eggs, and chorizo. Man, they have everything in those sacks! I’m watching the action when Grandpa comes out. He might still be mad, so I know I’d better get back on the bike to stay out of his way. He takes his hoe and heads out to his garden. I keep on riding around and watching Vampi’s family. They water the corn masa mix with water from the hose. Vampi begins rolling out the masa in a little plastic bowl. She looks nice now that she had her bath and fixed her hair and washed her feets.

Grandpa returns from the garden and in his hands, he has little baby zucchinis, which are not my favorite food, but one of my favorite words. The zucchinis have big yellow flowers on them, and it almost looks like he’s trying to be some kind of Romeo when he gives them to Yuritzi. She smiles and says gracias. The dad says, “I know we’re a bother. We’re grateful to you for letting us stay. We’ll leave soon.”

“We’re glad to help,” says my grandpa. “But you can’t stay long in this carport. It’s not good for you with children.”

“I know, señor. I know it’s not good.” They’re both quiet for a moment, then Grandpa says, “I’ll go and talk to the jefe right now. I think he can help you with some work.”

“We hope so, señor. We’re ready to work. We’ll do anything. Grandpa gets in the truck and closes the door. He rolls down the window and asks me if I want to go with him.

“No, Grandpa, I’ll play on my bicycle.” He leaves, and I stay. The mom has the frying pan real hot now, and she drops in the onions and the chorizo. The breakfast smell is so good and chorizo is my number-two favorite smell after peanut butter. They’re getting excited now, talking and laughing even, except I can’t understand what they’re saying. Sometimes I hear Spanish—“chorizo” or “trabajo,” but then it is not Spanish at all. I have never heard this language. She cracks the eggs and they land in the red chorizo like six suns. She pops them and the yellow goes everywhere, and she stirs it all up. She looks at me and smiles. I smile too. Finally the chorizo is done and they take it outta the fire. Vampi’s been making tortillas like crazy, throwing the masa from one hand to the other until they look nice and round. She’s flipping them with her fingers, and they look good. Dang. Vampi’s a good cook for a little kid. I tried making tortillas once, and mine came out all lumpy and shaped like shoe bottoms.

When the food is all made, they begin rolling little egg and chorizo taquitos with their hands. They lick their lips and their fingers even. It looks really fun, like camping. I smile at the mom again, and she smiles back. She rolls a taquito and passes it to Vampi. They talk their language, so I can’t understand. Vampi stands up and walks over to me. She takes my hand and puts a little chorizo taco in it. I can see her little bat teeth when she smiles.

“Thank you. Gracias,” I say. I take a bite and it’s so tasty I have to take another before I’m finished with the first one. We all start laughing, cuz it’s good and everybody knows it. I’m about to finish it off when Nana calls to me.

“Niño!! What are you doing?”

“They gave me it, Nana.”

“Get in here. Now!”

“Señora, we are happy to share with him,” says the mom. “We have plenty.”

“Gordo, get in here now,” says Nana again.

* * *

I go into the house. She looks like she can’t decide if she’s gonna cry or shout.

“You took food from them?”

“Yes, Nana. They gave it to m—” WHAM!! She slaps me across the face. She has never hit me there. We look at each other’s faces. I can’t believe it. She looks like she can’t believe it either. I feel like I’m gonna cry, but I know everybody gets mad at me when I cry, so I don’t.

“Can I go now?” I ask.

“Go,” she says. I go to the living room and turn on the TV. It’s the stupid news. I don’t care. I lay on the sofa with my face in the crack. I hear the family laughing and eating outside. I hear Nana in the kitchen. I try not to move or make any noise, but I can’t help it. The wet rolls down my cheek and into my mouth. I taste tears and egg and chorizo.

Cookie

Fat Cookie takes a tiny yellow library pencil out of her pants pocket. She looks from one side of the camp to the other, like a spy. She stares at the white wall in front of her like it’s something interesting: a television show or one of those flea market posters of the most beautiful unicorn with a gigantic tail, running in the wind. With the back of her hand, Fat Cookie wipes a dusty spiderweb off the wall and then holds the tip of her penc

il against the wall.

“What are you gonna do?” I ask her. She breathes.

“I’m thinking.”

“Are you gonna write on the wall?” I ask. “Because if you do, you’re gonna get in trouble with—”

“Shut up, idiot,” she says to me but not in a mean voice, just tired, like a mom.

“Gordo, what do you even know about trouble?” she adds. “You don’t have enough imagination to get into trouble. You’re too busy kissing ass and reading your books.”

“Fat Cookie, all the buildings in the camp belongs to Gyrich Farms. Even the outhouses. Besides, people live in this building, dummy. Tia lives there. Don Ramon. Heck, I’ll bet it’s against the law to write on that wall. You can’t just grab your pencil and draw—”

“Maybe you can’t, but I can, and I will. And don’t call me Fat Cookie, cuz you’re a fatty too.” Cookie puts her big moon face right up to mine. I can smell her.

“You always smell like peanut butter,” I tell her. “Is that all you ever get to eat at your house?”

“No. Sometimes we get the big block of cheese or the giant cans of tuna or chicken meat. What do you care anyways, you jealous?”

“No. Your mom can’t even cook good,” I say. “I saw her throw some meat in Wonder Bread and call it a taco. Meanwhile, my mom makes good food all the time. Fresh tortillas, pancakes, carne asada, pozole, chicken soup. Dee-licious.”

“That all you ever think of, food?”

“No.”

“Well it looks like it. I’m trying to start my drawing now, so shut it or I split your lip.”

“Go ahead and try, Cookie. You split my lip and—”

“You’ll what, bozo?” she asks.

“You split my lip and I’ll kick you,” I say. “Probably in the pussy!” Cookie wrinkles up her nose, like she smells something bad.

“In case you don’t know,” she says, “it doesn’t really hurt that much if you kick a girl down there. All it’ll do is make me mad, and then I’ll have to kick you in the coconuts. If you got any. See if that finally shuts you up.”

Gordo

Gordo